Sligo dock workers carry sacks, from the painting “The Gang” by Jack Yeats.

9,500 words 50 minute read.

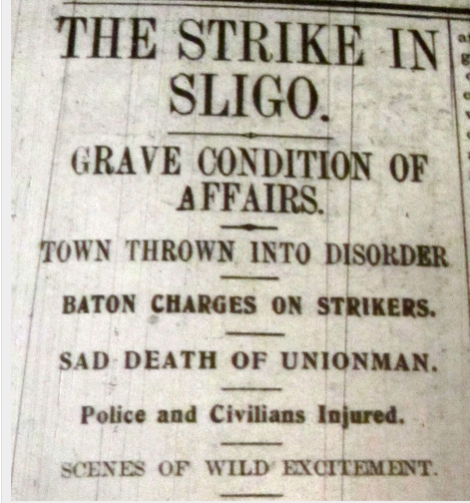

The 1913 lockout and strike in the port of Sligo in northwest Ireland was a labour dispute lasting 56 days from 8 March to 6 May 1913. During the strike, there were numerous clashes on the docks, riots in the town, extensive damage to property. In battles between strikers and strikebreaking labour gunshots were fired and one man was killed. Hundreds of soldiers and RIC were drafted in to deal with the unrest.

The repercussions of this and the other major incident of that year, the Dublin Lockout, were to have a lasting effect on the future trajectory of Irish history.

Strike!

It began the year before in 1912, when after a short strike, the workers had succeeded in organising labour on the docks under the new ITGWU union. Walter Carpenter had come to Sligo to organise the ITGWU in 1911 and the local Union representative, John Lynch was a member of both the sailors union, the NUASF and the ITGWU.

This union, the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) had been founded by James Larkin in 1909, this new type of union was successful in organising the “unskilled” and casual labourers that had not before this been represented by the craft unions. They made up the vast majority of the towns workers, and lived and worked in appalling conditions. Sligo had rates of TB double the national average, the worst in the country, which was saying something in those days. Housing was without sanitation or clean water and was in many cases exposed to run off from slaughter houses, graveyards, manure piles and tanneries.

The main employer on the docks, Arthur Jackson, of the Sligo Steam Navigation Company, a company founded by W B Yeats grandfather William Pollexfen, was determined to break the newly organised workers.

Jackson was a veteran union breaker, and had successfully prevented them organising since the 1880s and was determined to win this time also, so when on March 8th 1913 the seamen of the SS Sligo demanded more wages he saw his opportunity to break the new union and so, refusing their demands, proceeded to “lock them out”. Basically they were fired while the owners tried to source alternative labour.

“The Bay Pilot, The River Pilot, The Stevedore, The Ganger And The Gang” —The full cast of Sligo port workers as painted by Jack B. Yeats circa 1900, Model Niland Gallery, Sligo

The sailors were joined by deckhands and firemen. Several of the sailors were imprisoned for abandoning their posts. Now we see what Jackson was so afraid of, the sympathetic, or general strike, in which workers across industry struck in sympathy with those in other trades, this was the technique of the ITGWU.

Hence the strike now spread to the docks as the dockers joined them also. Jackson “locked out” all the unionised workers and sent his stevedores to recruit strikebreaking labour from Liverpool, but the arrival of this “scab” labour only heightened the tensions. As they tried to break the picket line, fighting erupted and a man Patrick Dunbar was struck and killed in the fracas.

The Sligo Champion reported that “things have now assumed an aspect which grossly threatens the commercial prosperity of the port and the town generally“. Quite whos prosperity was threatened it didnt say.

By the 22nd the firms carters ceased work also, and Jackson had to send his office clerks to man the horses. More police and army were brought into the town and now rioting erupted and shops and property of several firms attacked. Shops were boycotted and all non union labour was picketted. Countess Markiewicz`s brother Jocelyn Gore Booth shut his factory in the Market Yard. That goods could not be moved to and from it, was the official story, but its likely he locked out the 80 women workers also as the employers tried to maximise the pressure on the “union-men”.

The workers across the whole town now had to face down the hostility of the church, the police, the army, the GAA and Sinn Fein as the strike and lock-out continued into May. Perhaps surprisingly, and for reasons that will hopefully become clear later, they also had to go against the established unions which opposed the methods of the ITGWU and advocated a less radical approach.

The stand off rumbled on, with talks seemingly getting nowhere, until quite suddenly, on May 5th, Jackson and the other employers came to terms, the most important being that the ITGWU was recognised as legitimate representation for the workers. “The Irish Transport Union has won a complete victory”, the RIC County Inspector reported to Dublin Castle.

By January 1914 “The majority of newly elected members were put forward by the Trades Council and the local branch of the Transport Union so that the Council is now principally composed of Labour representatives”, said the Sligo Champion.

After much bitterness, fighting and even the death of a striker, they had won. But more importantly, they had implanted socialist ideas and action into Sligo culture, something the town was to pay a heavy price for in later years when the Free State came into being, but, for now, the workers, though with a long way to go, had achieved something quite remarkable.

This victory was regarded as a very important achievement of the ITGWU by Jim Larkin. Here was vindication that the approach of the ITGWU was correct.

Even as the Sligo strikes were ending in favour of the workers, the biggest battle in Irish labour history was already beginning in Dublin. Connolly and Larkin and the whole union movement felt encouraged, and hoped to replicate this success in the bigger arena of Dublin.

The Great Unrest

Sligo`s story was part of a wave of strikes, lockouts and agitation that spread throughout the industrial societies of the world between 1910 and 1914. The era was named the Great Unrest in Britain, great because of the ferocity of the confrontation and the violence used by the state and strikers as the conflict unfolded.

This was a different form of organised resistance than people like Arthur Jackson had encountered before in the previous century, consisting as it did in the general strike.

In Ireland it became disparagingly known to its enemies as Larkinism, after the founder of the ITGWU, Jim Larkin. As conservative nationalists like Sinn Féin president Arthur Griffith said

“The consequences of Larkinism are workless fathers, mourning mothers, hungry children and broken homes. Not the capitalist but the policy of Larkin has raised the price of food until the poorest in Dublin are in a state of semi-famine. The curses of women are being poured on this man’s head.”

But Larkinism was merely a euphemism to mask a worldwide movement called Syndicalism.

ITGWU

The ITGWU was a Syndicalist inspired union (Syndicale just means union in French). Jim Larkin founded it in 1909 and James Connolly, returning from the US, was appointed as Belfast organiser in 1911. Sligo`s Branch No.5 was organised the following year.

He set about organising the workers with mixed success during 1909. Eventually organising a sudden strike on Belfast Docks over pay. The story recounted by Connolly, and his description gives a vivid picture of the conditions in which people worked at the time.

“All day long in the suffering heat of a ship’s hold the men toil barefooted and half naked, choked with dust; while the tubs rushed up and down over their heads with such rapidity as to strain every muscle to the breaking point in the endeavour to keep them going, and with such insane recklessness as to be a perpetual menace to life and limb. Add to this inferno of industrial slavery that the men could not even retire to attend to the wants of nature unless they paid a substitute to take their place, that a visit to a WC or a drinking fountain often entailed dismissal, and that every slave-driving foreman or lick-spittle “master’s man” had a free hand to apply the spur, and the reader will have some conception of the depths of degradation to which our unfortunate Belfast brothers were reduced.“

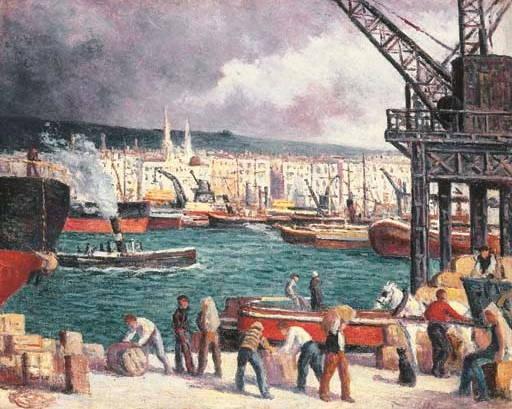

Maximilien Luce

Syndicalism sought to organise all workers into federated unions or into “one big union”. Often referred to also as Industrial Unionism, the term Connolly preferred, and which accurately describes its organisation based on industry as a whole.

Unlike the earlier craft and trade unions it included so called “unskilled” workers, general labourers and those on piece and day work, and used the method of the general strike to achieve its aims. Connolly said that the Industrial and craft union are mutually exclusive terms, emphasising this as a new development in the social movements of the time.

The ITGWU rapidly won 20-25% increases in the wages of its workers, a success that caused consternation amongst the employers. But these improvements were to be stepping stones on a radical program reorganising society itself from top to bottom, or bottom to top, more accurately.

“The Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union is in the vanguard of that Irish branch of the Army of Labour, and we are honoured when we carry its banner. “

His strike in Belfast resulted in better pay and conditions for the workers. The organisation, knowledge and small victories spread.

But it was not to last, within a few short years of its greatest successes Syndicalism was to be eclipsed by other forces and the countervailing philosophies of nationalism, authoritarian Marxism, the conservative crackdowns of the state and the convulsions unleashed by the outbreak of World War One.

Many since have criticised the actions of these times. That either the approach was wrong, that they were not political enough, too idealistic, or too naive, and many other judgements.

Our point of view more than a century after these events cannot help but be coloured by our knowledge of what happened since.

But we must strip away this knowledge of the future to get a glimpse of the “climate of ideas” within which people lived at that time. The difficulty, in any age, is that action in the present moment is always uncertain, and people must make their best guess of the right course in the moment, and always with imperfect information.

We can have some appreciation of the odds that were against them in these battles, the bravery that it took to fight for rights that seemed unattainable. We also see that despite the obvious setbacks, they often achieved more than they realised at the time.

To understand the intentions and beliefs of Connolly, Larkin and Mann and the thousands of people who believed in their vision, joined them and fought with them, often putting their lives on the line for the vision of a new society, we need to understand the background to Syndicalist unionism, and why it was regarded as such a threat to the establishment.

Utopia to Anarchy

Syndicalism was born out of the socialist movements, but socialism means different things at different times, so we must ask what was its dominant currents at this time? The period roughly leading up to the First World War.

Mention socialism now in 2022, and the image is generally that of Classical Marxism and Communism. familiar from the regimes of Russia, China and Cuba and many others in the 20th century. The source of the “Red Scares” and other fears of the “commies” so prevalent during the Cold War. This has come to define socialism, certainly in the American mind, and popularly elsewhere. But Marxism is not the source of Syndicalist beliefs.

Instead, Syndicalism had developed from Libertarian Socialism, a branch of thought that predated Marx, and while accepting of Marxs titanic economic analysis of capitalism, was most fervently opposed to the political ideas of Karl Marx, Syndicalism had in fact grown out of the ideas of the other great stream of socialist philosophy, the Libertarian, or Utopian Socialists.

The Utopian Socialists

Socialism took its modern form as a doctrine in the 19th century as one of a number of responses to the rapid rise of industrial societies and the huge problems of excess poverty and wealth this created in human societies.

The great immiseration of huge numbers of people and the enormous wealth of a few, as well as slavery, the desperate working conditions of the new heavy industries, the lack of rights of women and cruelty to animals all provided graphic demonstration of increasing injustice despite the supposed “progress” of mankind during the 18th century.

Increasingly it became obvious that the often ancient institutions of the state itself stood in the way of progress and protected the privileges of the few against the many, often with vicious force and lethal consequences.

The rediscovery in the 17th century of the Ancient Greek atomic theory of Epicurus and Democritus had sparked a revolution in science by stopping the fruitless attempts to transform base metals to gold. With the adoption of the atomic theory of nature, a physics, the leaps forward were astonishing. Surely, some thought, the same method could be applied to human social systems? After all, werent humans also the product of nature? Well, the Church of course disagreed, and here we have the first bifurcation between the new scientific rationalism and the older social systems inherited from the Middle Ages, the Age of Kings and feudal lords.

Rationalism gave rise to economics as the attempt to make a science of wealth and money, and to strip away the feudal privileges that enforced inequality on the masses. From Adam Smith to Marx the natural laws underlying markets, money and the generation of wealth were studied.

But what of the moral implications of this new knowledge? Why pursue it if only the few were to benefit? And if only the few benefitted, surely at some point inequality would become so great the many would overthrow the few, and what would come after that?. Nobody knew.

Well, as with Atomism, perhaps the Greeks had an answer also for this? Epicurus, writing in the 4th century BC, in his ethics laid out a scientific approach to judging human behaviour, motivation and the criteria for what is moral. This surely could be a starting point for a science of human society.

He taught that as living beings, we can judge right and wrong only by our senses. What is pleasurable is the greatest good and what is painful is evil. The subtlety was he defined “pleasure” as simply the absence of suffering. and taught that all humans should seek to attain ataraxia, meaning “untroubledness”, a state in which the person is completely free from all pain or suffering. This approach was called Hedonism. But they called it Utilitarianism at the time to mask its pagan origins.

Here was something they could work with, Using Epicurus` Hedonism (Utilitarianism) as a measure of morality, philosophers such as William Godwin and Jeremy Bentham began to measure the utility of laws and actions based on whether they increased pleasure or pain.

Bentham applied the idea to society rather than the individual, and came up with his “fundamental axiom”, the principle that “it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong.“ Here then was a moral motive, a target to aim for, and a way to measure the rights and wrongs of all questions of social and political policy and law. Now laws could be questioned, do they increase the happiness of the greatest number of people? Or only the few? Well, clearly, much of the law inherited from the medieval state was not exactly sympathetic to the majority, to put it mildly, and so they set to work to design a better, more rational, more scientific, and more just society.

William Godwin (he was father of Mary Shelley of Frankensteins fame incidentally) provided a critique of government in what is regarded as the first anarchist text in 1793 with his “Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Morals and Happiness” in this he laid out his 8 principles, three of which for example are

“The object of moral and political discourse is how to maximize the amount and variety of pleasure and happiness.“

“Reason’s clarity and strength depend on the cultivation of knowledge. The cultivation of knowledge is unlimited. Therefore, our social condition is capable of perpetual improvement; however, institutions calculated to give perpetuity to any particular mode of thinking, or condition of existence, are harmful.“

“The cultivation of happiness requires that we avoid prejudice and protect freedom of enquiry. It also requires leisure for intellectual cultivation, therefore extreme inequality is to be avoided.“

Here is clearly the Utilitarian method of analysing society in full view, measuring everything against happiness. The idea of more equal distribution of wealth and power as necessary to increase happiness became a corner stone of the developing movement and led to the first co-operatives and unions.

By the 1820s wealthy mill owners such as the Welshman Robert Owen were supporting “co-operative villages”. HIs practical implementation of the Utilitarains concepts was to be a turning point, bringing the ideas from the few philosophers to becoming a true mass movement. The three elements that emerged were the co-operative enterprise, the trade union, and the labour exchange. Many experiments were tried at this time, including at Ralahine Commune in County Clare, but the earliest and most famous was at New Lanark near Glasgow.

He and Bentham funded the New Lanark co-operative. This community of 2500 lived and worked around a mill, and Owen set out to apply the Utilitarian ideas to these peoples lives. Here the first infant school in Britain was opened in 1817, He limited the hours people worked and ensured a clean environment, and as he improved the conditions the mill became famous with dignitaries from all over Europe visiting to see this experiment. Not so impressed were his business partners who complained of the extra expenses his improvements cost. He bought them out.

Owen proved, much to the astonishment of his visitors, that a business could be profitable and treat its workers well. A novel concept indeed. Owens approach was referred to as Owenism, his followers as Owenites. But soon, there was another word used that better explained their aim of a better society, socialists.

However, Owen was no theorist, and there were indeed several issues with his approach. His appeal was to the rich who he felt could be persuaded to accept less profits. He did not think that the poor themselves could organise or that they should challenge the systems that kept them oppressed. He advocated that the ruling class would be the ones to change society, from the top down. Naturally, he was popular with this part of society, and was lauded by them on a speaking tour of Ireland during the Famine, something that was noted by his critics.

The flaws in Owens approach were pointed out by a member of Irelands Protestant Ascendancy, a landlord himself, but a most unusual philosopher of Utilitarianism. William Thompson of Cork was influential in his analysis of economics and an early advocate of full rights for women, something that not all socialists, not least Marx, could get to grips with in the 19th century.

But Thompson went much further than this. He recognised that it wasn`t in the interests of the capitalist owners to truly bring about a new society. “As long as the accumulated capital of society remains in one set of hands, and the productive power of creating wealth remains in another, the accumulated capital will, while the nature of man continues as at present, be made use of to counter-act the natural laws of distribution, and to deprive the producers of the use of what their labour has produced.” he said. Further, he said that As long as a class of mere capitalists exists, society must remain in a diseased state. Whatever plunder is saved from the hand of political power will be levied in another way, under the name of profit, by capitalists who, while capitalists, must be always law- makers.” He laid out the corrupting influence of excessive wealth as reason enough in itself to distribute wealth more evenly throughout society.

He therefore said that the capitalist society should be replaced by a co-operative socialism, but that this could only be brought about by the workers themselves.

Thompson introduced from France the idea of industrial organisation as necessary to this project, and he recognised the trade unions as “by far the most important movement” of his time. In his 1827 book, Labour Rewarded, he therefore argued that the trade union movement should not restrict itself to wage negotiations and should should be at the forefront of setting up the co-operative movement. He also criticised trade unions that excluded unskilled workers.

Maximilen Luce

The majority of the early socialists believed that either reform or that the building of the co-operatives would lead to the new society.

But as Thompson had pointed out, those who owned the capital also made the laws, and they by and large were not interested in a more even distribution of resources in society, which would obviously reduce their profits, at least in the short term.

Faced with this resistance to change from the establishment many came to increasingly believe that a revolution was required to really change society. But how this was to be achieved is the recurring issue.

The fundamental disagreement was simple. Should change come from the top down through the already existing power structure, the state and its ruling class? Or should change come from the bottom up, from the workers and poor themselves building a new society within the shell of the old and eventually replacing it.

The disagreements between Thompson and Owen were of this nature and were to continue with the development of a more revolutionary socialism as the 19th century wore on. Here, impatient at resistance, resort to confrontation and violence if necessary was increasingly seen as legitimate ways to force social change.

Proudhon

Around 1829 at the same time as Thompson was writing in Cork, a man arrived in the shop of a young printer in France named Pierre Joseph Proudhon. This man, named Fourier, was looking to get his latest book printed Le Nouveau Monde Industriel et Sociétaire. Fourier was a libertarian socialist and philosopher like many of his generation that Marx would dismiss as Utopians. Fourier’s concern was to liberate every human individual, man, woman, and child, in two senses: education and the liberation of human passion.

Proudhon was influenced by Fourier to pursue philosophy. He published his first work, What is Property? in 1840. Then A Warning to Proprieters, a book for which he was put on trial, but then acquitted as the jury would not condemn someone for a philosophy it could not understand. In 1848 Proudhon wrote the System of Economic Contradictions, or the Philosophy of Poverty.

In this book Proudhon wrote of the relation of the individual to the state, and formalised what early philosophers had pointed at but not explicitly followed though on. The states monopoly on violence meant that it effectively blocked any attempts to create a fairer society.

Proudhon rejected all political action, and argued that workers could achieve a better system through economic action alone; He advocated abstention from politics, as the real aim of socialism must be the ultimate eradication of the state. Proudhon was the first of the new socialists to call himself an anarchist.

The response was immediate, and from an unlikely quarter, a young German writer who had initially sought to collaborate with Proudhon, but now launched a scathing attack on Proudhons book, releasing a response termed “The Poverty of Philosophy”.

Karl Marx, background was very differnet to Proudhon, who incidentally his doctoral thesis On the Difference between Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature.

It was Marx who first disparagingly referred to the early socialists as Utopian Socialists, to contrast their approach also with his materialist philosophy, a “scientific” socialism.

But, as we have seen, from the beginning, socialism itself was born out of the philosophy of science, and specifically out of the very Ancient Greek materialism that Marx himself studied in university. Why was he so keen to be seen as different to those who went before?

Marx was combative, falling out with Proudhon when the latter kept his distance and refused to castigate a mutual friend that Marx had fallen out with. Marx immediately began a vendetta against Proudhon, claiming he was afraid Proudhon would “mislead the masses”, although it seems more likely he was concerned Proudhon would eclipse Marx in the socialist movement that Marx desperately wanted. Marx spared nothing in his vitriol, writing an entire book not just to refute Proudhon, but to destroy his character and bury his ideas.

He claimed he was incapable of abstract thought, didn’t understand philosophy or economics, was an idealist, that altering the social system without first destroying it was impossible, that he did not comprehend the historical process and that his individualism was abhorrent.

In contrast, Proudhon never really responded publicly to Marx attacks and provocations, though privately he did refer in his diary to Marx as “the tapeworm of socialism”. Overall Marx`s attacks did not have the intended effect until many decades later.

Proudhon did not believe in the necessity of revolution for social change and thought change could be accomplished without resorting to force. Proudhon, thinking of historical revolutions within his lifetime in France of 1789-99 and 1830, and in 1848, was very wary of promoting it as a method of change, believing revolution often became perverted into a travesty of its intended form.

A truly successful revolution, he thought, would come from evolutionary transformation of the morals and philosophy of mankind.

Proudhon rejected all political action as a form of class collaboration arguing that the working class through economic action alone; abstention from politics was advocated with a view to the ultimate eradication of the existing state and its political apparatus.

Here was the basic tenets of anarchist thought and the syndicalism that developed from it. The turning away from politics and emphasis on economic action put the unions at the forefront of the strategy for change. It also amounted to a strategy of boycott of the existing system by refusing to engage in it by the organisation of political parties.

Here again, like in the previous generation, the conflict was between the advocates of top down change and those that advocated it from the bottom up.

The next stage of socialism emerged from the First International Working Mans Association, the first international gathering of mutualists, socialists, trade unionists, communists with a view to creating a mass movement in 1864. This association sought to unite the various social reform and revolutionary movements of the time, it resulted in a split between the two different main approaches to achieving progress.

While the tendency was to become more revolutionary rather than reformist.

Marx and his dogmatic and deterministic philosophy had quickly come to dominate the International.

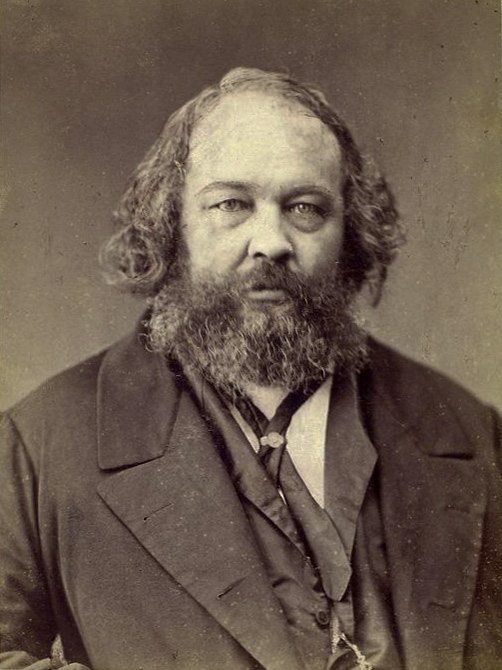

Bakunin

In 1872, a crisis erupted at a meeting of the International in the Hague which split it into two broad factions, one that coalesced around the economist Karl Marx, and that which formed around the chief anarchist theorist, the Russian Mikhail Bakunin.

The Marxists advocated the political approach, believing the way forward was through politics and the state, the so called “state socialists” or Marxists. Marx and his faction therefore did not emphasise the role of trade unions, instead aiming to take over the state politically and create a “Dictatorship of the Proletariat” in which a workers party, would reorganise society from the top down.

They advocated, in the words of Trotsky later “authoritarian leadership, centralised distribution of the labour force, the Workers State as preeminent power” and the vanguard Communist Party as sole arbiter of the revolution.

Marxism was to become the dominant form of socialism after the Russian Revolution in 1917, and therefore the most well known to us to this day. But in the time period we are looking at these events lay in the future,

The Libertarian Socialists formed the largest group in the First International. They were descended from the early ideas of Bentham, Godwin and Owen and and through Proudhon and Bakunin they mutual and the collectives an co operatives and credit unions.

It was this form of socialism that was dominant reaching its zenith from the 1890s until about 1925. Its revolutionary current of Anarchism, and its practical offshoot, Syndicalism were to be the defining revolutionary movements of the first decade of the 20th century.

Anarchism

Anarchism, from Ancient Greek Anarkhos, meaning “without a ruler” simply the “no-government form of socialism” or more formally defined in the Oxford dictionary as “belief in the abolition of all government and the organization of society on a voluntary, cooperative basis without force or compulsion.”

The Anarchists objected to political organisation of the workers as counterproductive. As Kropotkin, a major anarchist theorist put it,

“the state, having been the force to which the minorities resorted for establishing and organising their power over the masses, cannot be the force which will serve to destroy those privileges”.

The anarchists believed the state could never create a more fair society, but was the very source of the unfairness they sought to abolish.

Kropotkin, who after Bakunins death became the most influential anarchist philosopher also objected to Marx`s claims to have discovered historical “laws”, saying they were “political and social astrology“ and of no more predictive power than “the claims of those wise women who pretend to be able to read the destinies of man in teacups or in the lines of the hand.”

Liberty, Bakunin said, required “social and economic equality“, and that “the people will feel no better if the stick with which they are being beaten is labelled the “peoples stick”.

Its worth looking at Bakunins own words on why he opposed Marx`s political approach, and what the anarchists stood for. This excerpt is from his influential book Statism and Anarchy.

“In accordance with this belief, we neither intend nor desire to thrust upon our own or any other people any scheme of social organization taken from books or concocted by ourselves.

We are convinced that the masses of the people carry in themselves, in their instincts (more or less developed by history), in their daily necessities, and. in their conscious or unconscious aspirations, all the elements of the future social organization.

We seek this ideal in the people themselves. Every state power, every government, by its very nature places itself outside and over the people and inevitably subordinates them to an organization and to aims which are foreign to and opposed to the real needs and aspirations of the people.

We declare ourselves the enemies of every government and every state power, and of governmental organization in general. We think that people can be free and happy only when organized from the bottom up in completely free and independent associations, without governmental paternalism though not without the influence of a variety of free individuals and parties.

Such are our ideas as social revolutionaries, and we are therefore called anarchists. We do not protest this name, for we are indeed the enemies of any governmental power, since we know that such a power depraves those who wear its mantle equally with those who are forced to submit to it.

Under its pernicious influence the former become ambitious and greedy despots, exploiters of society in favour of their personal or class interests, while the latter become slaves.“

So the Marxists sought to create a new society from the top down, the anarchists from the bottom up. There was to be no meeting in the middle.

The crisis came to a head in 1871 when in a meeting in London, Marx had inserted, in response to the defeat of the revolutionary Paris Commune, a resolution on the necessity of a workers political party as the means to a socialist revolution.

“That this constitution of the working class into a political party is indispensable in order to ensure the triumph of the social revolution and its ultimate end — the abolition of classes.”

Karl Marx 1871 – Resolution No. 9

This resolution, along with the other fundamental differences, caused an immediate negative reaction amongst the majority of the International.

At the next meeting in 1872 in Holland, Bakunin, who could not make it, was expelled in absentia by Marxs faction who had gained control of the General Council. With the split now official, both sides claimed (and still claim) to be the true descendants of the First International, but from then on went their separate ways.

From then on the anarchists and Marxists, pursued fundamentally different approaches to socialist revolution. Marx`s influence was strong in Germany and England, the anarchists in Switzerland, France, Italy and Spain. But in general until WWI the libertarian socialists were the largest grouping in socialism.

Mother Earth Anarchist Magazine 1914

The anarchists, in keeping with the “bottom up” method of organisation, inherited the idea the trade unions as instruments of change from the earliest days of the Utopian socialists and William Thompson.

So it was from the conjunction of anarchism and the unions that the next development of the means of wresting change was perfected.

Syndicalism

A member of the First International, Lois-Eugene Varlin, a Parisian bookbinder had included in the statutes of his bookbinding union he had founded in 1857 that it should be dedicated “to the constant improvement of the conditions of existence of the workers of all professions and all countries, and to [bringing] workers into possession of the instruments of their labour”

On November 14, 1869, Varlin helped found the Parisian Federation of Workers’ Associations, a confederation of trade unions that became the nucleus of the General Confederation of Labour (CGT), the main organisation of the French syndicalist movement.

Varlin had led his union into the First International, where he had taken the side of the Proudhonists with Bakunin and ended up joining the Paris Commune insurrection for which he was shot in 1871. About 20,000 of the Communards as they were known were massacred by the state during the insurrection. This drove the nascent Syndicalist movement underground for a while, but also led to he radicalisation of socialism in general, as the argument of peaceful evolution seemed unrealistic with such levels of state violence. But his work lived on in the Confederated unions that spread throughout France in the last few decades of the 19th century.

Maximilien Luce

Between 1895 and 1910 Syndicalist unions, such as the CGT in France, spread rapidly throughout the industrialised world, being particularly in Spain, Italy and France.

But the aims and philosophy of the Syndicalists went much further than demands for better conditions or higher wages, although these were fought for and won at the time.

The Syndicalists envisioned a world after capitalism, a federation of democratic assemblies with the factories and workshops owned by the workers. Borders between nations would be dissolved, and democratic cooperatives would share the fruits of labour to each according to need. Utopian sounding (it would be) perhaps, but Syndicalism represented the practical plan to get there.

The federated unions were to provide the nucleus of this new way of organising an advanced industrial society. To achieve their aims the Syndicalists sought to unite all workers across society and internationally so they would strike in sympathy with each other, eventually resulting in a universal general strike which would bring about the replacement of the centralised state with a new socialist organisation of society.

In other words, Syndicalism aimed at the dissolution of the centralised state and the transference of ownership of industry to the workers, a full revolutionary socialist program. But what made it dangerous was, it knew how to go about it.

The outcome was to be achieved incrementally, step by step as workers educated themselves and became aware of what their unified strength was capable of. The first step of course, was recognition by employers of the right of workers to organise and be represented by their unions. Next, were demands for better pay and conditions, for example the 8 hour work day was campaigned for and won at this time.

in the 1880s the Eight Hour League was formed by a socialist named Tom Mann in the British Social Democratic Federation (SDF), a union that included William Morris and James Connolly amongst its members. Mann and Connolly met in the 1890s and kept in touch.

In 1910 Mann travelled to France where the largest syndicalist union existed, the CGT (General Confederation of Labour) and returned convinced that their doctrine was the right approach. Mann founded the International Syndicalist Education League(ISEL) to educate people on the philosophy and methods of the movement.

He also started publishing The Industrial Syndicalist that year and reached out to other union leaders to join his new group, one of which was named James Larkin. By 1910 both men were committed Syndicalists.

Meanwhile, Connolly had been in the US since 1903, where, on a similar trajectory from party based socialism to syndicalism he had ended up as one of the founders of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The major Industrial Union of the United States founded in 1905.

“There is on foot a great world Movement, aiming definitely and determinedly at the economic emancipation of the workers.” wrote Mann.

Another Tom Mann pamphlet printed in 1910 was titled confidently “The Way to Win”. Whether in Sligo or Liverpool, or the hundreds of other workplace disputes erupting at the time, Syndicalism had started to bring success against the owners of industry and the state that supported them.

Increasingly, the future that workers had fought for seemed to be within reach, if only they could hold their nerve and apply themselves to growing the movement.

- A preference for federalism over centralism.

- Opposition to political parties.

- Seeing the general strike as the supreme revolutionary weapon.

- Favouring the replacement of the state by “a federal, economic organisation of society”.

- Seeing unions as the basic building blocks of a post-capitalist society.

Syndicalism was the practical method of achieving change without putting political action at the forefront, developed out of the philosophy of the libertarian socialists and anarchists from the very beginning of socialism in the late 18th century.

It was this form of socialist philosophy that dominated the early years of the 20th century, a time later known as the Golden Age of Anarchism and Syndicalism.

In Ireland, a land in which neither the industrial revolution nor the Enlightenment had seemingly had much impact, the ancient struggle of its people to be free of subjection by the British Empire was about to be changed forever. James Connolly had returned to Ireland, this time not as a young British soldier, but as a man who had developed his own analysis of Irish history and society and most importantly, he believed he knew how to change it.

James Connolly

James Connolly, born in Edinburgh in 1868 in an Irish emigrant slum called “Little Ireland”. Like his older brother, joined the army at 14 to escape poverty.

He served, as far as can be ascertained, in the 1st Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment arriving in Cork in 1882. Connolly mentions being on guard duty when Myles Joyce (Maolra Seoighe)* was hung on the 15th December 1882 in the infamous Maamtrasna murder case in which three men were sentenced to death on flimsy evidence and notoriously tried in English despite them speaking only Irish.

So from the moment he arrived the Land War was in full swing, a situation that undoubtedly had a major effect on him. The regiment was involved in evictions, in riots in Belfast and eventually was stationed in Dublin where it ( very interestingly considering Connollys later 1916 role) took part in exercises simulating an insurrection in the city.

By the 1890s Connolly was demobbed, back in Scotland, and his career as a socialist organiser had begun. He took over as secretary of the Scottish Socialist Federation after his brother John was fired after making a speech in favour of the 8 hour day. He was a prolific organiser and founder of papers and pamphlets. And because of this, he was offered and accepted the job as organiser of the Dublin Socialist Club. Now, by this stage his ideas on both socialism and the need for Ireland to separate from the empire were well developed. In order to consciously link the two, he created the IRSP ( Irish Republican Socialist Party).

Now, to stand back and see where we are, much has been written on the ideas of Connolly, and it`s impossible to do justice to the scholarship of a century in this glance at history. But it is the case that in the main, analysis of Connollys philosophy has been through the lens of either nationalism, whether republican or otherwise and/or through socialist historians. And of the socialist commentaries, they are overwhelmingly of an authoritarian Marxist point of view, this being the dominant form of socialist thought in Britain and Ireland in the later half of the 20th century. This has led to some confusion in the analysis of Connollys beliefs.

It has been claimed for example, that he was purely a revolutionary Marxist, but that his ideas were vague on how to achieve that revolution. That he wavered in beliefs, flirting briefly with syndicalism, but then taking a turn to nationalism and the Rising. Both Connolly and Larkin have been criticised for neglecting to focus on a revolutionary party, for being too focussed on unions. They have been regarded as naive in not understanding the necessity of a political focus to take over the state in the vent of revolution, and so on.

What many of the criticisms have in common is a certain mapping of concepts that would in fact come later, like Bolshevism, Leninism, Trotskyism onto Connolly and his time. Marxism is the wrong lens through which to analyse Connolly, Larkin and the Ierish labour movement.

But, if we simply follow the thread as we have laid it out in this essay, I think it shows that Connolly is in fact consistent throughout his career.

The key is to understand that Connolly was fundamentally a Libertarian Socialist, who understood and accepted Marx`s economic analysis, but who was not dogmatic in his interpretation of Marx. He therefore consistently followed the line of the libertarian and anarchist socialists in advocating the primacy of building a new system from the bottom up.

He referred to himself as both a socialist, and as an Industrial Unionist (Syndicalism), and Syndicalist principles run consistently through all of Connollys writings. From the 1890s, the Syndicalists had been influenced more and more by anarchists as they abandoned the tactic of “propaganda by the deed”, violent assassinations and the like that had generally backfired.

The syndicalists were placed in direct opposition to the Marxist program of nationalization of industry, electoral activity, and the centralization of both the First International and the state. And in each case Connolly is perfectly aligned with the Syndicalists.

What we can chart is a growing sense of the need to overthrow the capitalist system directly, and a growing confidence in how to do that. If anything his thought moves along a trajectory from the political party to that of an almost out and out rejection of politics as a realistic method of change, and eventually culminating in the armed revolt of 1916.

So, as early as 1898 we see him argue on the subject of nationalisation of industries such as telephones, railways and canals he points out that “we would, without undue desire to carp or cavil, point out that to call such demands ‘Socialistic’ is in the highest degree misleading. Socialism properly implies above all things the co-operative control by the workers of the machinery of production; without this co-operative control the public ownership by the State is not Socialism – it is only State capitalism.“ This is the position first taken by Bakunin in the First international and one of the core criticisms of Marx`s statism by the anarchists at this time.

In 1903 Connolly went to America where he was to take up a job with SLP (Socialist Labour Party) run by Daniel De Leon. De Leon had been a believer in state socialism, (Lenin later commented that the Bolsheviks had adapted De Leons idea of Marxism). De Leon had begun to be interested in the new Industrial Unionism especially pioneered by the miners of the western United States. In 1905 Connolly and De Leon were part of the foundation of the IWW.

The IWW used the slogan One Big Union to unite all industrial workers throughout sectors and across the world, and the General Strike as the weapon of choice to effect change. Although it claimed to be uniquely American, the IWW was (and is) a classic Syndicalist Union with ties to socialist and anarchist movements in particular.

It was not long before there was conflict between Connolly and De Leon, which became publicly fought out in published letters.

They differed on issues of womens rights, and on religion, but the core of the argument revolved around an argument on the “Iron law of Wages” which basically said that every wage increase won would be cancelled straightaway by a rise in prices.

This was anathema to Connolly as it threatened the basis of unions as the key to the reorganisation of society. “The theory that a rise in prices always destroys the value of a rise in wages sound very revolutionary, of course, but it is not true. And, furthermore, it is no part of our doctrine. If it .were it knocks the feet from under the S.T. & L.A” The ST & LA was a general union, and here Connollys concern is that such a position would undermine the primacy of the unions in the socialist movement.

The argument eventually split the IWW with De Leon setting up his own faction in Chicago.

Again the argument was the always repeating one that divided the Marxists and anarchists in First International. What is of note here is that Connolly, again, sided with the anarchists on the issue of union primacy in the socialist struggle.

In his pamphlet Socialism Made Easy, written in 1908 while he was in America, Connolly quoted the following from an American campaigner A M Stirton

There is not a socialist in the world today who can indicate with any degree of clearness how we can bring about the co-operative commonwealth except along the lines suggested by industrial organization of the workers.

Political institutions are not adapted to the administration of industry. Only industrial organizations are adapted to the administration of a co-operative commonwealth that we are working for. Only the industrial form of organization offers us even a theoretical constructive socialist program. There is no constructive socialism except in the industrial field.

About the above quote Connolly writes that this “so well embodies my ideas upon this matter that I have thought well to take them as a text for an article in explanation of the structural form of Socialist Society“

Connollys years in America were formative, and from his above commentary we can see he had a clear vision of the society he was aiming for and the method for how to bring it about. This vision is that of the federated unions as forming the nucleus of the post revolution society. Indeed the anarchists referred to this future organisation as The Federation. The founders of Spanish anarchism for example claimed that the labour organisations would replace the state and that, “the Federation would rule”

They saw the industrial unions as the both the training ground and as the new system itself being built within the shell of the old, until such time as it replaced it. Connolly is clear that the old style politics cannot achieve this, and cannot be the way that the new society is organised. In this again he is in accord with the anarchist conception. In Socialism Made Easy he wrote,

“Under Socialism states, territories or provinces will exist only as geographical expressions, and have no existence as sources of governmental power, though they may be seats of administrative bodies.”

By marrying anarchist philosophy to the grassroots organisation of the industrial unions Syndicalism created a sophisticated social force, one with more power than either would have on its own. Connolly understood this perfectly well.

“Here we have a practical illustration of the power of Socialism when it rests upon an economic Organization, and the effectiveness and far-reaching activity of unionism when it is inspired by the Socialist ideal.”

Ireland

In Ireland, there were added problems. Connolly had to work out how to sell his vision in a country which had taken a different trajectory to most of western Europe. To do this he had to find parallels to Irish experience.

Ireland had, under the yoke of colonialism, by and large missed out on the Industrial Revolution. Most of the country had remained rural and was under absentee landlords. Except in the port towns, there was no “working class” in the industrial sense that Marx had written about.

Here his experience of the Land War enabled him to explain the General Strike as being essentially the same concept as the Boycott perfected in Mayo during the Land War. This was something the Irish could understand, and that could be applied both rurally and in the towns.

Next, in terms of the core Syndicalist idea of federated unions organised confederations of industries he linked to the re-emerging knowledge of Gaelic Irelands decentralised and democratic political organisation. Indeed, many Irish still lived naturally, albeit unrecognised officially, in this same way, in federated tribes or clans with elected leaders. After discussing the Gaelic organisation of society and common ownership of land Connolly writes,

“The Irish System was thus on a par with those conceptions of social rights and duties which we find the ruling classes today denouncing so fiercely as ‘Socialistic’.

It was apparently inspired by the democratic principle that property was intended to serve the people, and not by the principle so universally acted upon at present, viz., that the people have no other function in existing than to be the bondslaves of those who by force or by fraud have managed to possess themselves of property.“

In these instances it was the ideas of the anarchists that most closely matched the political and historical conditions in Ireland, Whether Connolly chose them because he knew this, its impossible to tell, but as he adapted them or chose those best suited to Irish history and understanding. He was nonetheless effective in welding the ancient reason for Irelands resistance to English domination to a forward looking social vision, and he did this by recognising that even the ancient conflict had revolved around fundamentally different concepts of property.

It is clear, when looked at this way, that there is really no conflict between Connollys socialism and the Gaelic revival, and the idea there is, only arises later through misunderstanding.

It is worth quoting at length Connollys outline of his vision from Laboour in Irish History in 1910.

“Add to this the concept of One Big Union embracing all, and you have not only the outline of the most effective form of combination for industrial warfare to-day, but also for Social Administration of the Co-operative Commonwealth of the future.

A system of society in which the workshops, factories, docks, railways, shipyards, &c., shall be owned by the nation, but administered by the Industrial Unions of the respective industries, organised as above, seems best calculated to secure the highest form of industrial efficiency, combined with the greatest amount of individual freedom from state despotism. Such a system would, we believe, realise for Ireland the most radiant hopes of all her heroes and martyrs.”

Connolly advocated a federally organised state and recognised that the old Gaelic organisation of Ireland which had existed until the 17th century was stateless and consisted of federated territories called tuatha, organised into confederate groups. What unified them was adherence to a universal code of law.

Connolly, therefore was a Syndicalist in both belief and action, a position that put him quite firmly within the libertarian anarchist tradition of the First International. In this sense his ideas cannot be understood without reference to the thinkers of this tradition, from the early Utopians all the way to Bakunin and Kropotkin. Connolly of course was also someone who had fully imbibed and understood Marxs importance, but the anarchists had also accepted in large part Marxs economic arguments without reservation. Where they differed with Marx was in the means of achieving the socialist project, and in this Connolly was identical to them.

“This leads me to the last axiom of which I wish you to grasp the significance. It is this, that the fight for the conquest of the political state is not the battle, it is only the echo of the battle.

The real battle is the battle being fought out every day for the power to control industry and the gauge of the progress of that battle is not to be found in the number of voters making a cross beneath the symbol of a political party, but in the number of these workers who enrol themselves in an industrial organization with the definite purpose of making themselves masters of the industrial equipment of society in general.“

And understanding the idea that change came only from the bottom up, that political engagement was not the first line of the battle, but only the echo of the battle, it becomes less difficult to understand his supposed turn to armed insurrection in 1916, he was merely staying true to the same principles he had all along, and kept right up to 1916.

Contemporaries must have recognised this as in 1916 the Dublin Chamber of Commerce was to claim that the Rising was a revival of 1913 activism. They werent exactly wrong.

Postscript

The Sligo strikers won recognition of their union in 1913, but in 2022 Under Irish law there is no obligation on employers to recognise trade unions and there are no plans to bring forward legislation to provide for mandatory trade union recognition.

The events of 1913 Sligo Dock Strike and subsequent Dublin Lockout were the high point of the Irelands Syndicalist revolt. Subsequently, the character of events was to take a different turn, with the outbreak of war in 1914 changing the character of societies permanently.

In general, the war itself and the events following were in many senses a counter-reaction to the advance of radical socialism, and the very real gains it was making for the mass of people who toiled in the awful conditions of the 19th century. With Syndicalism the program of the old Utopians had the practical tools to realise its vision, effectively without force. This made it a real threat to the traditional structure of power.

In Ireland the forces of the counter-revolution gained the ascendant with help from England, and the regimes that became the Free State and Northern Ireland were to erase from memory the aims of the 1913 strikers, Syndicalism became merely Larkinism, Connolly was just an unrealistic communist, the new narrative painted the aims of revolt as purely a nationalist movement and not internationalist as Connolly had intended. The many women who had fought, were put back in their place by an ultra conservative Catholic hierarchy.

For towns like Sligo and many others, the two new states that emerged were to have a catastrophic effect. Everything the workers had stood for in 1913, now marginilised them after 1922. The conservative forces of the new state now in power, were precisely those that had fought the workers during the strikes, The Catholic Church, the GAA, Sinn Fein, the Civil and public service. The Old English and Irish Catholic middle classes and elites that had flourished under the 19th century British empire had re-asserted control. A revolution pf sorts had occurred, but it was firmly from the top down.

Even Sligos business owners who had in 1913 compromised and recognised the ITGWU in Sligo now found themselves quietly shut out, and so for the majority of the towns people the new state led to poverty, marginalisation, abandonment and emigration.

In the words of the eccentric founder (and self professed anarchist and puncher of DH Lawrence) of the Irish Citizen Army along with Connolly, Jack White, the 1916 “rising is now thought of as purely a national one, of which the aims went no further than the national independence of Ireland”. “The true nature of this revolution, was conveniently forgotten”.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Notes

Ralahine Commune – an unusal experiment in co operative village in County Clare Ireland. The co-operative issued its own currency as well as a having a cooperative general store.

*Maolra Seoighe was posthumously pardoned by Micheal D Higgins in 2018

anarcho-syndicalism, the now classical anarchist school of thought, Noam Chomsky stated that it remains “highly relevant to advanced industrial societies”

Sources

LABOUR v. SINN FEIN. The Dublin General Strike 1913/14 – The Lost Revolution

“Lucien van der Walt “Industrial Union is the Embryo of the Socialist Commonwealth”: The International Socialist League and Revolutionary Syndicalism in South Africa, 1915-1920

Lucien van der Walt – Black Flame Vol. 1

https://blog.nli.ie/index.php/2013/03/08/sligo-dispute/

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/rocker-rudolf/misc/anarchism-anarcho-syndicalism.htm#s3

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/bakunin/works/1873/statism-anarchy.htm

“An Inquiry into the principles of the distribution of Wealth most conducive to Human Happiness as applied to the newly-proposed System of the Voluntary Equality of Wealth.” William Thompson, 1824

Eric Hobsbawn

James Connolly – Socialism Made Easy – 1906

James Connolly- Labour in Irish History – 1910

Pat O`Sullivan – William Thompson: The First Irish Socialist 2012

Robert Hoffman (1967). Marx and Proudhon: A Reappraisal of Their Relationship. 29(3), 409–430