Image: Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto | Architect Daniel Libeskind Berlin

In 2016, after 65 years in the town of Sligo, the Nobel medal of WB Yeats was removed from the little proto-museum attached to the library in Sligo town. This medal had been donated by William Butler Yeats son, Michael, and it is presumably the case that he knew that his father would have wanted the medal to be on display in Sligo. The medal was removed because Sligo does not have an accredited museum to store such artefacts.

In 2015 nine rare bronze 16th century cannons from as far away as Barcelona and Dubrovnik in the east Meditarranean were lifted from the seabed off Streedagh. They could not be conserved here and had to be sent to Dublin where they remain. They will never come back here without a suitable museum. In fact the list of artefacts from all eras of Irish history and all types that are held elsewhere and cannot be brought back is very long, and continues to get longer.

Sligos missing museum results in an incalculable loss both economically and culturally to the entire region. But it also seems to be the case that this is not well understood. There are currently proposals to build a Yeats Interpretive Centre, and of course all ideas to develop heritage are to be welcomed. But there is a problem. A museum is basic cultural infrastructure, and without it. the development and updating and accessibility of Sligo heritage is severely restricted.

The difference between a museum and an interpretive centre is fundamental. One is infrastructure, the other is an amenity. They are not interchangeable. Its worth comparing the definitions of the two words just to be very clear.

INFRASTRUCTURE – The basic physical and organizational structures and facilities (e.g. buildings, roads, power supplies) needed for the operation of a society or enterprise. “the social and economic infrastructure of a country”. —— From Latin infra ‘below, and structure to build. So that which underlies our systems and facilities.

AMENITY – a desirable or useful feature or facility of a building or place. “the property is situated in a convenient location, close to all local amenities” —— late Middle English: from Old French amenite or Latin amoenitas, from amoenus ‘ pleasant

So before you can build swimming pools or shopping centres you must put in roads and power. A museum represents the roads and power for the cultural sector. The reason for this is it is an accredited archaeological repository. This means it can hold, conserve, acquire and display real historical artefacts, something no other facility can do. A museum contains the conservation laboratories that allow the conservation and treatment of archaeological artefacts from the past, both those we have now and those yet to be found. As cultural infrastructure a museum actually supports and allows the creation of other cultural enterprises by providing the basic facilities and expertise they need to operate successfully. In other words, all projects, including interpretive centres are possible after a museum is in place, but to build them before it will not work.

Due to these different functions interpretive centres cannot replace the role and expertise of a museum, and therefore they cannot have the financial and cultural impact of a museum. The reason for this is they are not licensed to hold real historical and archaeological artefacts, and without that ability they are restricted in scope.

missing museum

Leaving aside the Model Arts centres original granting as a museum, Sligo almost had a museum built 14 years ago. A museum foundations lie behind the hoardings that stand to this day at the top of the Connaughton Road. Dating to the time of the Celtic Tiger, the project was begun and abandoned in 2007, with the Global Financial Crash, Sligo County Council also sank without trace, failing to return any accounts to central government for two whole years and becoming the most indebted council in the history of the Irish state. A grant for the museum of 2.9 million euro was switched to the Model Arts centre at this time, while it was claimed there was “no money” for a museum. At the same time Sligos new library was also shelved.

Of course this means there is still no accredited archaeological facility in the northwest, (the Museum of Counrty Life in May deals with 19th century folk collections only) which means, as our history covers thousands of years outside this, that like the Yeats Nobel medal mentioned above, we continue to lose more and more of our heritage every year.

other projects cannot be supported

This loss of a museum has been negative for all heritage projects in the region. Projects on the Greenfort, where the nature of the remains is not conducive to on-site development are held up by the lack of a museum to hold exhibitions. The Armada project in Grange, while looking for their own display space, would find it a lot easier if there was a museum to back up with loan of artefacts and expertise. The recent closure (June 2021) of the degree course in archaeology in Sligo IT can in part be traced to this failure to have a museum facility in Sligo.

The spin off from having the artefacts in Sligo is not just in having a tourism facility in the heart of the town. These artefacts inspire the arts, they are paths into the history for children in education, they provide material for scientists to learn and practice techniques and develop world class expertise in.

Sligos archaeological and cultural heritage is enormous, spanning 8, 000 years, but the loss of the material remains has also been enormous. The ravages of colonialism have taken there toll and much of Sligos material history is scattered all over the UK and Ireland. Much of it of course is in Dublin, most of course is not on display, and never will be, as the National Museum just doesnt have the space.

To get an idea, and its just an idea, of the broad historical themes a museum in Sligo will have to engage with and the amazing artefacts that come from this region but are held elsewhere, the following is a selection.

stone and bronze ages

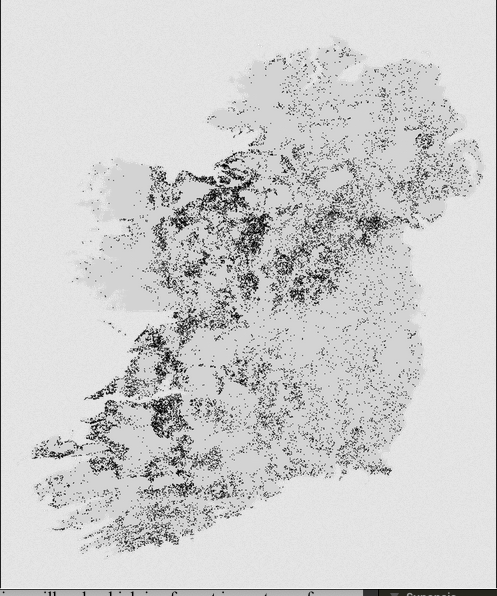

Sligo comprises only 2.5% of the land area of Ireland, yet it contains 15% of all known megalithic structures, perhaps the highest density anywhere in Britain or Ireland. 12% of all court tombs, 6.3% of all portal tombs, 7.5% of all wedge tombs, and an amazing 40% of all the passage tombs known in Ireland.

Sligo is the only place in Ireland where all types of monument occur together. There are multiple sites on Knocknarea which are laid out in a similar fashion to Newgrange

Carrowmore has the oldest form of passage graves known in Ireland, and is therefore unique, there is no other site like it. Also, of the four major passage tomb complexes in Ireland, two are in Co. Sligo. At Magheraboy the oldest known Causewayed enclosure in Britain or Ireland was found during road excavations, dating to 4100 BC. Sligos Neolithic archaeology alone would warrant a museum to itself.

The area was densely enough settled to be known to Greek and Roman trading vessels being marked on Ptolemy‘s co-ordinate map of the 2nd century AD, where it is entered as the town of Nagnata. This is the only settlement marked on the west coast of Ireland by Ptolemy. It is possible traders were attracted by the silver and lead mines on the coast at Ballysadare.

gaelic sligo

The local Irish tuath, or territory, was called Cairbre Drom Cliabh or Críoch Cairbre. Another, older name, according to Acallamh na Sénorach, the “Dialogue of the Ancients” was Críoch an Cosnámha (The District of Battles). Its age is unknown, but it appears to have acquired the name Cairbre in the 5th or 6th century AD.

Ringforts, raths and monasteries abound in the landscape and the names of the territories and landforms are gateways into the mythology which is rich.

The two great Gaelic poets from Sligo Muireadach Albanach O Dalaigh and Tadhg Dall O Huiginn, masters of Dan Direach (Direct Verse) are both of international importance in their time, the 13th and 16th centuries respectively.

the manuscripts

The Medieval Gaelic town of Sligo is highly unusual in being the seat of an urban Gaelic culture throughout the Middle Ages. This is unique in Ireland. It is because of this unique situation that many manuscripts were written and collected in this region before the fall of Gaelic civilisation in the 17th Century. Here the O Connors, the Orourkes, the MacDonaghs the O Haras the Ogaras, the ODowds and Mac Sweeneys all played their part in shaping the story of medieval Sligo.

A large amount of Irelands ancient literature is preserved in books written in the northwest of Ireland, particularly in the Sligo region. In some cases the only surviving copy of some texts. The scholar Dubhaltaigh Mac Fhirbisigh of Lackan in west Sligo set about saving much of the ancient lore about the time of the Cromwellian wars, writing in the Book of Genealogies (a compilation of Irish genealogical lore relating to the principal Gaelic and Anglo-Norman families of Ireland and covering the period from pre-Christian times to the mid-17th century)

If there is anything in it deserving of censure apart from that, I ask him who can to amend it, until God give us another opportunity (more peaceful than this time) to rewrite it.“

Dubhaltach Mac Fhirbisigh 1650

He wrote the above words on the 28 December 1650, just as English parliamentary forces, completing the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, crossed the Shannon. Half the population did not survive this war.

- The Great Book of Lecan,

- The Yellow Book of Lecan,

- The Book of Ballymote,

- The Great Book of Genealogies,

- The Poem-book of the OHara,

- The Annals of the Four Masters,

Not one of these books are now in this region.

If even a portion of them was to be returned it would place Sligo as a centre for Gaelic scholarship for the future, as it had been in the Middle Ages.

the yeats family

Sligo has many famous connections, from Charlottes Stokers inspirational account of the Cholera epidemic, to Harry Clarkes mother who also grew up in Sligo. But the family most associated in the modern era is that of Yeats.

All the Yeats family were artists and contributed to Irelands nascent Arts & Crafts movement, ther importance to the entire history of the new state cannot be overstated. . The sisters Elizabeth and Susan who were well ahead of their time running the printing presses in Dublin on which many of their brothers books were printed. Jack Yeats, in hos own right is an artist of international reknown, and lesser known but no less important is his role in the development of the modern comic. W B provides an unparalleled link between Sligo and the worlds literature, as well as the complex history of colonialism and nationalism, and we are lucky to have an institution that examines these things in the long running Yeats Summer School. The Yeats Society is housed in a building associated with the Pollexfen family.

However, even as we recognise WBs contribution to world literature, we mus trecognise something he himself would have insisted on, it is all drawn on Sligo. A place that his mother always assumed to be the most beautiful in the world. It would be a mistake to celebrate Yeats and not the heritage that he himself drew on and all his life sought to highlight.

the armada wreck-site

The Armada wreck site is so extensive it warrants its own post, but it must be known that this is probably the most important 16th century military wreck site in the world. Three ships fully equipped for the conquest of Britain were buried in the sandbanks of Streedagh beach. Much of the wreck site appears to survive, and looting and recovery did not happen at the time as the war agains Queen Elizabeth and Dublin raged for 15 years after their loss preventing recovery.

All were large transports laden with material for the marine invasion of England, carrying soldiers, their equipment, and material for the siege and capture of London . Spain fielded the most advanced and best equipped army of its day. The three ships that were grounded here we know quite a bit about.

- La Lavia (25 guns). 728 tons 71 sailors 271 soldiers 355-568 tons Carrack Venetian merchantman from Naples. Vice-flagship of the squadron.

- La Santa Maria de Vison de y Biscione) (18 guns).70 sailors 236 soldiers 350-560 tons Ragusan (now called Dubrovnik) merchantman. 666 tons.. Armada medical supplies were transferred to her from the Casa de Paz which was condemned as unseaworthy during the voyage.

- The Juliana (32 guns) 860 tons Built in 1570, she had 65 crew 290 soldiers estimated 325-520 tons burthen Catalan Barcelona merchantman., this ship was perhaps carrying siege train parts ie tools and potentially heavy guns for use against fortifications. hence cannon recovered with the Matrona of Barcelona Genoese gunfounder Gioardi Dorino II

These details allow us to estimate what was wrecked on that day in September 1588. We can count 807 soldiers and 206 sailors, for a total of 1013 personnel altogether. But, the Santa Maria de Vison was acting as a hospital ship, we remember, which means the likely number of soldiers on board is probably higher and most of these would have been unable to escape. The total weight of the three ships displacement is 2254 tons of cargo and structural timber. This is equivalent to 112 modern steel shipping containers.

As a rough comparison, Henry VIIIs flagship the Mary Rose, recovered from the Solent in 1984, was also a carrack albeit a big one. Only one third of this ship survived on the seabed and yet archaeologists recovered 26,000 objects and pieces of timber from this site. At the wreck site at Streedagh we have three ships of roughly 700 to 800 tons each. The site is orders of magnitude larger than the Mary Rose.

“Though similar vessels have been excavated, the initial investigations hint at an unparalleled level of preservation not only in organic remains but in articulated hull structure”Unlike most Armada wreck sites they are accessible. .

why a museum may not be a matter of choice

But there is a serious reason that we must plan our cultural infrastructure now or face losing this resource to the rest of the world forever. With most sites in the state they are stable, being buried on land, or even in deep water at sea. But in this case its in a very active area, the coastline.

The site being full onto the Atlantic is unstable, disturbed by storms most years. Every so often material is exposed. Every time the site is threatened it must be excavated by the state archaeology sector as it is a protected site. The law requires archaeological intervention to prevent the loss or destruction of archaeological material. This means that as time goes on, the site has to be excavated. There is no choice or option in this.

And so we must plan to recover, conserve and display the artefacts and perhaps even the ships hulls that will likely have to be recovered in future from this site in the future. Good quality storage facilities, with appropriate environmental conditions and sufficient space are essential to protect the condition of the collections. If we dont we will be in breach of the National Monuments Acts if material is lost, and even if material is recovered every single bit of it will leave Sligo forever if we do not plan ahead.

No County museum we envisage right now will be big enough to display the Armada material alone, or store it. So I would suggest that a site is reserved in Sligos docklands which has the space to handle ships timbers of large size. The site must be beside landing facilities at the quay in Sligo, and requires storage facilities that have access to salt water and are large enough to contain, in theory, three full scale Armada transports each with a 100 foot long keel. Another advantage of this location is access to the rail head allowing the transport of large and heavy artefacts in and out of Sligo as required, a likely scenario as a project on this scale is inevitably an international affair involving the Spanish government.

This will require us to start building the expertise and facilities needed to deal with this over the next century. Sligo must develop expertise in marine archaeology dive teams, submersibles, scanning technology, the ships that can recover large objects from the ocean. Objects recovered are likley to be all sorts of material from the 16th century, all of which will require expert conservation. Expertise in scientific appllications in archaeology can be developed through Sligo IT archaeology department, with the museum collections providing the material on which to develop world class expertise.

regenerating Sligo docklands?

A site should be acquired on the quays whether or not its decided to place a museum there. The current plan envisages a museum alongside the new library between Stephen street and Connaughton road. Placing them beside each other has advantages, not least the eventual return of Sligos manuscripts should also be planned for, and with ancient books the line between museum and library is blurred and they may benefit through being integrated.. No matter what it is decided on to build first, its important to think in the long term when it comes to heritage and cultural infrastructure. The making available of funds for the building of a museum and library is a welcome development.

The workers on the docks, the women workers in the textile factories on the Per mill Rd. and Market Yard. The story of the Dock Strike in Sligo where the workers won an important victory against the owners and that inspired the subsequent Lockout strikes in Dublin. Here we come full circle as one of the major owners was Pollexfens of the Sligo Steam Navigation Company, Yeats maternal family. The history of the town in the 19th century and the 20th century. the industrial area of the docks Sligo town is a neglected but important one to tell.

museums create cities

Museum of Liverpool is “challeng[ing] preconceptions of the city, breaking down prejudice and feeding into regeneration strategies, to raise community aspirations and promote positive citizenship”

NML, 2008

Museums are economically transformative to the cities in which they are placed, having a large if indirect economic benefit. There are many examples of the regeneration of cities through the building of flagship museums The Guggenheim in Bilbao is a famous example that was intended, and succeeded in regenerating the city starting with its neglected docklands.

Museums have the ability to present the stories of those traditionally left out of the narrative. Current exhibtions in the Museum of Country Life document the stories of women migrants currently living in Mayo, and importantly, are able to do so with a historical context often missing in other forms of presentation.

Understanding the history of Ireland is also central to breaking down barriers with the Traveller community and creating a balanced narrative of the past, something that has been lacking in modern Irish history.

“The traditional mission of a museum is essentially cultural. However, it is not like this for all museums. There are a minority, although universally famous museums, like the Tate Liverpool, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, the Tate Modern London, or the new forthcoming Louvre-Lens (France), Pompidou-Metz (France), Guggenheim-Hermitage (Lithuania) and Guggenheim-Abu Dhabi (United Arab Emirates), whose principal aim is the re-activation (and/or diversification) of the economy of their cities.”

So, I want to pose the question of what the city museum can do as a part of the ongoing creative process of a city that is forever changing and being re-created. How can the museum of the city join the design energies and the political energies and the bureaucratic energies and the private sector energies and the people in a city as a civic lens to contribute to the form and personality and quality of that city – not just as an observer but as an actual player?

If Sligo wishes to be a city it needs to engage with its past and its future and begin a conversation now on how to integrate the two. The effects of the destruction and dislocation of culture under imperial occupation, and as a border area are still keenly felt in the region, and result in a lack of ownership and sense of possibility of what Sligo and the northwest could be.

It has a unique and vast heritage that if understood can have a transformative effect, not just on Sligo, but on the northwest and the country. It is not intended to set out one right way to do things, but to lay out the magnitude and opportunity the past represents to Sligo, a past that if engaged with can be transformative to its fortunes. To do so will require thinking on a scale that, after a difficult few centuries is hard to envisage. But we used to think this way, and we can do so again.

The Royal Ontario museum pictured above is designed to reflect its environment. In this case reflecting an ice crystal, and also integrated with the cities past architecture. As an example of the type of thinking that may be required, a concept has been put forward by architect Darragh Murphy for a museum to reflect Sligos mythology and inspired by the shape of the dolmens at Carrowmore, with the capstone on basal pillars.

It is hoped this article gives some idea of the scale and scope of Sligos historical heritage, and stimulates a discussion on how best to plan to protect, recover and present that heritage to the world.

Whatever your opinion, have your say on Sligos future, submissions on your vision for Sligo can be made to Sligo County Council for inclusion in their 2030 plan and are open until 8th July.

https://www.sligococo.ie/2030/

Links

The City as Museum and the Museum as City –

https://omnimuseum.org/the-city-as-museum-and-the-museum-as-city.html

Bilbao as global leader in culture led regeneration –

Bilbao City- A Global Leader in Culture Led Urban Regeneration

Museums as economic drivers –

New National Data Reveals the Economic Impact of Museums Is More than Double Previous Estimates

Appendix

Council objectives, yet to be implemented, as laid out in Sligo County Council documents.

- ‘Establish County Museum with curator and support staff”

- “Appoint full time County Archaeologist with support staff””

- Appoint full time Conservation Officer with support staff””

- Carry out a survey and establish a database of Sligo’s archaeological objects”

- Integrate heritage appraisal into planning sections

- Geographical Information System (GIS)”

- Carry out a survey of buildings in Sligo associated with the Yeats family

- Promote heritage awareness through appropriate media”

- Establish County local history publication unit””

- Promote and develop the use of management plans for Sligo’s archaeological landscapes particularly Carrowkeel”

Tate modern regenerates London district

And in Rotterdam, Netherlands, the City Museum is working with the city and its communities as its ‘muse’.

3 responses to “Why Sligo Needs a World Class Museum”

A very good and impassioned plea. Let’s hope we can pull together and make it happen.

LikeLike

Great article Dylan!

A top-level museum would be a fantastic drawcard and much needed to safeguard and highlight the heritage of the area.

LikeLike

Excellent synopsis Dylan. Those 3 maps of Ireland illustrating the very high density of passage tombs, court tombs , and ringforts in North West Ireland make a compelling case for an associated museum in Sligo. I thought the Docklands would be the preferred location as it allows for a preplanned commercial residential and institutional precinct to complement a Cultural building in a waterside setting. A museum might not be built until much later due to economic realities but without the catalyst effect and provision for a major visitor attraction, the Docklands would likely fail to live up to its potential.

LikeLike